Calibrating Load Cells: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

|2.8318 || 6.14e-4 || 2.8312 || 0.00061 || 0.010% | |2.8318 || 6.14e-4 || 2.8312 || 0.00061 || 0.010% | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Long Term Usage of a Load Cell== | |||

While the calibration factor of your load cell will remain more or less constant, there are some external factors that can shift the zero-level offset of your load cell over time. To mitigate this, if you are able to unload your system and measure a new zero between measurements taken a few minutes apart, we recommend you do so. Think of it as pressing the ''tare'' button on your kitchen scale, which is there for exactly this reason. | |||

If, however, you need your load cells to be more stable over longer periods of time, we recommend checking our article on [[https://wwwdev/?view=articles&article=LoadCellCorrection Load Cell Correction]]. | |||

Revision as of 20:37, 18 November 2021

Due to manufacturing variations, load cells are fairly unique in the Phidgets product line as sensors that will require individual calibration to get meaningful results in an end application. Thankfully this process is relatively simple, as we will show here.

What is Calibration?

At the most basic level, load cells measure a real world force by converting it into an analog voltage measurable by a Phidget. Once the Phidget has measured the voltage and sent it to your computer, you can convert it back to units you can work with (e.g. N, kg, lbs). Calibration is the process of determining how to make that conversion. Luckily, in the case of load cells this is made easy by the fact that they are designed to send a signal directly proportional to the force applied. In simple terms, when you apply twice as much force, you will get twice as much output.

How to Calibrate a Load Cell

For most applications, load cells can be characterized in terms of a zero-level offset, and a conversion factor. The zero-level offset being the amount of signal the sensor produces under "no load" conditions, and the conversion factor representing how much the output signal changes for a given change in force. In this context "no load" is understood to mean the amount of force the sensor will see when the system is at rest.

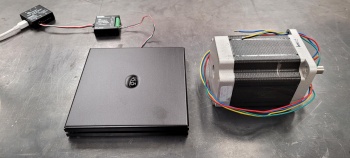

To demonstrate the process of calibrating a load cell, I will use the KIT4007 weigh-scale, with a load cell rated for a maximum weight of 5kg. You should always fully install the sensor in whichever system or application you intend to use it in before calibrating, just in case certain aspects of the construction have an effect on the measurements.

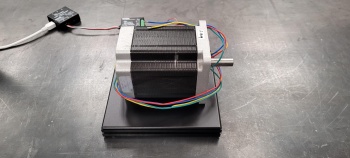

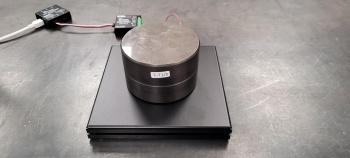

To begin calibration, we will take two measurements: one with the scale empty, and one with a known weight. Depending on the desired accuracy of your system, finding a known weight can be as simple as weighing an object on a trusted scale, and recording the weight. Here I've used a stepper motor which was weighed to be 3.5309kg.

|

|

For this example, we used the Phidget Control Panel example to manually read off the load cell readings.

| Weight (kg) | Reading (V/V) |

|---|---|

| 0.00 | 4.348e-5 |

| 3.5309 | 7.55e-4 |

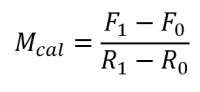

To calculate the load cell conversion factor (we'll call it Mcal), simply divide the change in weight by the change in sensor reading.

where R0 and R1 are the weights used, and F0 and F1 are the corresponding sensor readings.

Finally, to use your new-found calibration factors you can plug in new sensor readings into the formula:

where R0 is the zero reference measurement, R is the latest reading, and F is the corresponding calibrated weight (in kilograms, for this example).

Verifying the Results

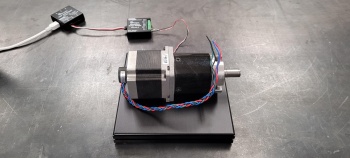

We can demonstrate the effectiveness of the calibration by applying different weights to the scale and checking the results.

|

|

| Weight (kg) | Reading (V/V) | Result (kg) | Error (kg) | Error (% of full-scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.4978 | 3.45e-4 | 1.4972 | 0.000522 | 0.012% |

| 2.8318 | 6.14e-4 | 2.8312 | 0.00061 | 0.010% |

Long Term Usage of a Load Cell

While the calibration factor of your load cell will remain more or less constant, there are some external factors that can shift the zero-level offset of your load cell over time. To mitigate this, if you are able to unload your system and measure a new zero between measurements taken a few minutes apart, we recommend you do so. Think of it as pressing the tare button on your kitchen scale, which is there for exactly this reason.

If, however, you need your load cells to be more stable over longer periods of time, we recommend checking our article on [Load Cell Correction].