OS - Phidget SBC

![]() On the Single Board Computer (SBC), Phidgets can be either plugged directly into one of the USB ports or run over a network using the Webservice.

On the Single Board Computer (SBC), Phidgets can be either plugged directly into one of the USB ports or run over a network using the Webservice.

Getting Started (Libraries and Drivers)

The SBC is a unique Phidget. It is a computer with a Linux operating system. It can compile code, save files, manage background jobs, host information over the web, and more.

To learn the basics about the SBC, we have a handy web interface to interact with the SBC. This is covered in detail on the Getting Started Guide for the SBC. So before reading this page on how to use the operating system, you should have done the following via the Getting Started Guide:

- Set up networking on your SBC, via either Ethernet or wireless

- Set up a password

- Learned the IP address or link local address of the SBC

Conceivably, you could simply use the SBC like any Linux computer, and do all of your development and compiling of Phidget code on the SBC itself. In practice this is quite complicated as the SBC does not have a keyboard or screen. So usually, you will want to develop your code on an external computer and copy files and settings over to the SBC via a network. This makes this Getting Started section unique, in that we show you how to set up both computers:

- Your External Development Computer, usually your main desktop or laptop which will transfer files and settings to and from the SBC

- The SBC itself, which needs programming language libraries to use Phidgets.

Getting Started - External Computer

You have two ways to connect to the SBC from an external computer: via the SBC Web Interface and over the more powerful but complex Secure Shell (SSH).

SBC Web Interface

You have already worked extensively with the web interface in the Getting Started Guide for the SBC. This was the tool within a web browser which was opened either via the Phidget control panel on Windows, or by simply entering the IP or link local address into the browser. It allowed you to set the password, set up internet connectivity, and so on.

We talk about the additional functionality of the web interface elsewhere in this document. This web interface will probably stay your initial go-to way to connect to the SBC, especially for tasks that benefit from graphical interaction, like setting up wireless or using the webcam.

SSH

The most flexible way to transfer files and commands to and from the SBC is via a program called ssh. The ssh program provides command line text access over a network into the SBC. Using it, you can run programs and give the SBC commands. The ssh program has a companion program called scp which can copy files back and forth. For Linux users, this will be familiar territory. If you are using Windows or Mac OS, and are unfamiliar with ssh, you can think of it like the command line or a Mac terminal.

Before connecting over ssh, you will need:

- The IP address (such as 168.254.3.0) or link local address (such as phidgetsbc.local) of the SBC

- The admin password for the SBC

Both of these items can be found by following the steps in the Getting Started Guide for the SBC.

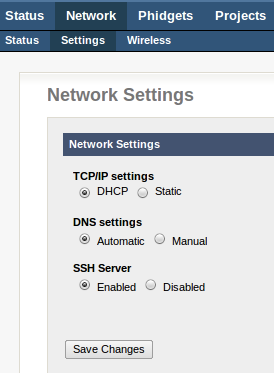

You will also need to enable SSH on the SBC side. This can be done through the Web Interface, under Network → Settings, by changing the SSH Server radio button to Enabled:

SSH on Windows

The ssh program is not installed on Windows by default. But, there are a variety of SSH programs available for free, one simple and commonly used program being PuTTY.

With PuTTY, when you first run the program it will ask you what to connect to. Enter the IP address or link local address of the SBC, and then click the SSH radio button right below the address, which will change the port to 22. Then click open, and you'll have an ssh connection to the SBC open in a terminal. It will prompt you for a user name (root) and password (the admin password).

To copy files back and forth, there is an SCP component to PuTTY, called PSCP, which is available from the same PuTTY download page.

SSH on Linux and Mac OS

Linux and Mac OS already have ssh installed by default. To run ssh simply open a terminal...

Ctrl-Alt-Ton LinuxApplications → Utilities → Terminalon Mac OS

...and type:

ssh root@phidgetsbc.local

If you have re-named your SBC, include that name instead of the phidgetsbc.local link address. Or, you can use the SBC's IP address, e.g. ssh root@168.254.3.0.

To copy files back and forth, the command follows the form of: scp from to

So, to copy a file /root/data.txt from the SBC to your local machine, type:

scp root@phidgetsbc.local:/root/data.txt .

Note the use of the dot . to indicate that scp should put the file in the current local directory. If you're not sure what folder the terminal is operating in type pwd to print the working directory. Terminals usually start by default in your home folder.

Getting Started - The SBC (Debian Linux)

The SBC comes with the following Phidget functionality installed:

- The Phidget C libraries

libphidget21.so - The Phidget Webservice

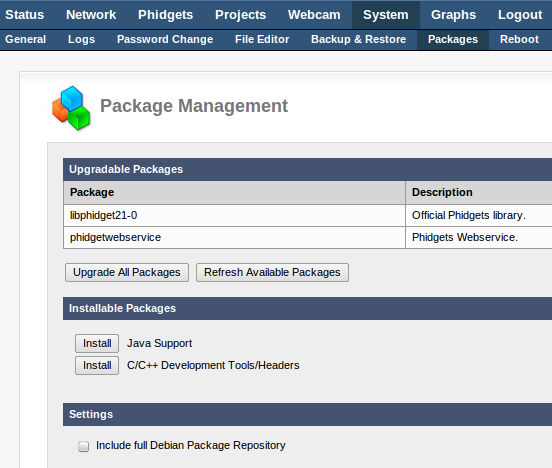

These packages can be seen via the SBC web interface

Installing C/C++ and Java

The simplest way to install C/C++ and Java on the SBC is via the web interface. There is a button under System → Packages to install C support (including gcc) and another button to install Java support. Clicking the Java button will also install C support, as Java depends on the C libraries:

Installing Python

Installing Python has two steps. First, you'll need to install the basic ability to run python, and then you'll need to install the Phidget Python module.

Basic Python

apt-get install python

Install Phidget Python Method 1: Use a USB Key

Copy the Python Libraries onto a USB key. Unpack the zip file into a folder on the USB key. Insert the key into the SBC.

You will have to figure out where the USB key (and the Phidget Python library folder) is now located. We describe how in the general Using USB Data Keys section.

After you know the place where the USB key is mounted, go to that directory (e.g. cd /media/usb0/, enter the unpacked Phidget Python Library folder, and run:

python setup.py install

Now, you're ready to begin writing Python code for the SBC. For more help on writing and using Python with Phidgets, we have an whole page on that topic.

Install Phidget Python Method 2: Use the Internet

Rather than using a USB key to transfer the file, the SBC can download it directly from the internet. You will need wget and unzip installed, both of which are small:

apt-get install wget

apt-get install unzip

Copy the web link address for the | Python Libraries.

In an SSH terminal to the SBC, type: wget http://www.python_library_link where instead of http://www.python_library_link you insert the link you just copied.

This will download the Phidget python libraries to the folder you ran the wget command in. Unzip the file using the command unzip.

Installing Other Languages

You may also be able to program on the SBC using Ruby and C# under Mono, though we do not offer in-depth support for these languages on the SBC. The installation procedures should more or less follow that of installing python on the SBC, except you will be installing Ruby or Mono. Performing package searches using apt cache search can help you find the relevant software.

Using SBC Linux

Now that you've set up communication with the SBC, and installed whichever programming language support you need, you're probably ready for a short tour of useful tools on the SBC's version of Linux.

First, you will by default be running on the SBC as root, which is the super-user. For experienced Linux users, this probably makes you nervous because you know you can overwrite important system files without the system asking for additional permission. Even as a Windows or Mac OS user - although you may usually run your computer as an administrator - the system usually prompts you to confirm before you do anything really dangerous, and this will not happen on the SBC as the root user.

Next, there is no installed help on the SBC. Help on Linux is usually called 'man pages' which is short for 'the manual pages'. On a full Linux system, usually if you need help with any command you can type, for example, man ls and it will give you help with the program ls. But these help pages take up significant space, and they are widely available online. So, if you need more help with a certain command, you can always type man command into your favourite search engine.

Finally, the SBC has no windowing system. For experienced Linux users, this means no X-windows (Gnome, KDE, etc). And as a Windows or Mac user, although you may not think of the graphical window interface as simply a front-end to the actual operating system, indeed it is. The SBC provides all of the functionality of an operating system (e.g. process scheduling, file management, etc) but without any graphical interface. The only exception is the web interface, which gives graphical access to a limited part of what the SBC can do.

Some Useful Commands

If you are doing more with the SBC than simply running pre-written programs in Java to run continuously from boot, you will be interacting with the SBC's Linux operating system over the command line by using SSH. This section discusses useful programs already installed on the SBC, and how to run them on the command line.

ls

The ls program lists the contents of a directory.

It will show both files and folders, but not files that start with a "." (these are hidden files on Linux).

- If you also want to show hidden files, use

ls -a - If you want more information, such as size and date modified, use

ls -l - Commands can be combined, like

ls -al

cd

The cd program changes to a new directory.

For example, cd /root changes into the directory at the base of the file tree called root.

Note:

- Linux uses forward slashes

- The base of all directories is "/" (not "C:\")

- The tilde symbol (~) is short for your home directory (i.e. when you are root, this is short for "/root")

- The double dot ".." means move one directory higher (for example from

/root/data/to/root/)

pwd

The pwd program prints the current directory you are working in. ('P'rint 'W'orking 'D'irectory)

For example:

root@phidgetsbc:~# pwd/root

find

The find program does what it says - it finds things.

Unfortunately for the casual user, the find program is very flexible and powerful, and thus not especially intuitive to use. But, here are some examples:

| SSH Command | What it Does | Example |

|---|---|---|

find folder -name file.txt

|

Looks for all files in a folder (/ for root - or all - folders) with a certain name (* for wildcard) | find / -name *.jpg

|

find folder -mtime +X

|

Looks for all files in a folder modified less than X days ago | find /root -mtime +30

|

grep

The grep program takes text input and searches for a term.

For example, if you type mount to view what devices are mounted (e.g. loaded) on your SBC, you will see:

root@phidgetsbc:~# mount

tmpfs on /lib/init/rw type tmpfs (rw,nosuid,mode=0755)

proc on /proc type proc (rw,noexec,nosuid,nodev)

sysfs on /sys type sysfs (rw,noexec,nosuid,nodev)

udev on /dev type tmpfs (rw,mode=0755)

tmpfs on /dev/shm type tmpfs (rw,nosuid,nodev)

devpts on /dev/pts type devpts (rw,noexec,nosuid,gid=5,mode=620)

rootfs on / type rootfs (rw)

procbususb on /proc/bus/usb type usbfs (rw)

/dev/sda1 on /media/usb0 type vfat (rw,noexec,nodev,sync,noatime,nodiratime)

This may be a lot of information you don't need. If you are only interested in a USB key attachment (as described in the Using USB Data Keys section), you can use grep to filter that one response:

root@phidgetsbc:~# mount | grep sda1

/dev/sda1 on /media/usb0 type vfat (rw,noexec,nodev,sync,noatime,nodiratime)

nano

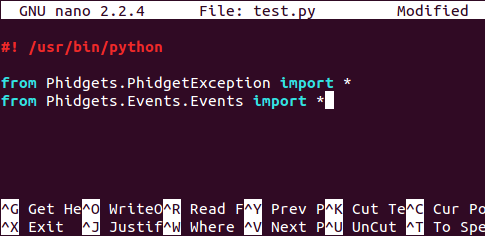

The nano program is a small text editor that you can use within an SSH terminal.

Nano can be surprisingly useful for writing short lengths of code right on the SBC, so there is no need to transfer files and keep track of different file versions on different computers.

Nano has all keyboard commands which are listed at the bottom of the screen at all times as a reminder (Ctrl-O to save, Ctrl-X to exit, these expand with a larger terminal window). And, nano provides what is called 'syntax highlighting', which colours reserved keywords, comments, strings, and so on as appropriate to the programming language you are using. Nano detects the programming language via the extension of the file (.java for Java, .c for C/C++, and .py for Python).

Typing nano test.py on an SSH command line and then entering a few lines of Python into the new empty file results in:

apt

The apt program allows you to install, uninstall, upgrade, and search software available for the SBC. For a non-Linux user, the apt framework may be daunting at first, but it actually allows you to keep your system up to date

| SSH Command | What it Does | Example |

|---|---|---|

apt-cache search term

|

Looks for all programs (packages) that have term in the title or description

|

apt-cache search opencv

|

apt-cache show package

|

Shows a lot of data about package including size, version, etc

|

apt-cache show unzip

|

apt-get update

|

Gets the most recent listing of available software | apt-get update (No options)

|

apt-get install program

|

Installs program from the internet

|

apt-get install python

|

which

The program which tells you if and where a program is installed.

For example, on a default SBC, typing which python will return no results. But after successfully installing python, it will return /usr/bin/python as the location of the python program/binary/executable.

Some Useful Commands to Install

These are other programs you may find useful on the command line. Although they are not on the SBC by default, these and other programs can usually be installed simply by using apt-get install, with the exception of gcc. For example, apt-get install wget will download and install wget.

Note: This section and the section on pre-installed commands can hardly cover all of the complexities and benefits of the Linux operating system. There are many excellent tutorials online, and between them and using apt to find and install programs you should be able to learn a lot and perform any number of complex useful tasks.

gcc

The gcc program is the C compiler for Linux.

If you are an experienced C/C++ user on Mac or Linux, or if you've already read our C Language page, you might think you need to install gcc via apt-get to compile C code. However, gcc is not in the package repository for the SBC, so apt-get install gcc will fail. Rather, to install gcc, you can do it via the web interface, as described in the Installing C/C++ and Java section.

After installing it via the SBC web interface, you can use gcc normally.

less

The less program displays the contents of a text or source code file. When displaying the file, less allows you to scroll up and down to read it.

This is useful if you are writing your sensor readings to a data file, and you want to read the data file while it is being written by your main code. If your data file is called data.txt, you can type less data.txt and see the lines in the file, and what they are.

The less program output can also be piped into another program. For example, you can use less and the word search program grep to find lines within a file with a search term. For instance, if you have a C source code file Program.c on the SBC, and you want to see all the lines in Program.c that contain a variable name var, you can type:

less Program.c | grep var

wget

The wget program allows you to get an online file (over http) and download it to the SBC.

For example, to get the source file (HTML) from the Phidgets home page, you can type:

wget http://www.phidgets.com

This is most useful for downloading libraries, drivers, or anything (zip, tar, etc) you need from the web which is not available by using apt.

Writing a Phidget Program

We provide two ways to write and upload a Phidget Program:

- The web interface, which is useful for:

- This is useful for simple projects written in Java that you want to start only at boot

- You can also use C projects, but they must be compiled off the SBC for an ARM processor

- Over SSH, which will allow you to write or transfer source code directly to and from the SBC

- This is useful for all other projects, such as:

- Projects that run at scheduled times (e.g. once per minute)

- Projects that use other languages

- This is useful for all other projects, such as:

Note that you can still run an SSH project at boot, you just have to write and install a startup script. This is a bit complex, but we do have an example that starts the program phidgetwebservice21 at boot using a script.

Once you know which method you'd like to use, you can continue on to learn how to Program in Java with the Web Interface, or how to Program with SSH using C or Python.

Program in Java with the Web Interface

To show how to write, compile, and install Java programs on the SBC, we'll use the Java Hello World example code. You can download the HelloWorld example by downloading the whole Java example package.

Here's how to get the HelloWorld code running on the SBC:

1. Download the SBC version of the Phidget Java libraries (phidget21.jar). You can download this from the web interface, on the page under Projects → Projects, under the Notes section.

2. Place the SBC version of phidget21.jar into a directory on your external computer. This will be your working directory that you will use to compile the Java files.

3. Also copy the HelloWorld.java file into that working directory.

4. Compile the HelloWorld.java file from within that working directory. From the command line prompt on Windows, this will be:

javac -classpath .;phidget21.jar HelloWorld.java

In a terminal on Linux or Mac OS, this will be:

javac -classpath .:phidget21.jar HelloWorld.java

5. You should now have three compiled class files: HelloWorld.class, HelloWorld$1.class, and HelloWorld$2.class. You don't need to try and run them, and if you do you may encounter an error because the SBC phidget21.jar may be slightly different than the Phidget support you have installed on your external computer.

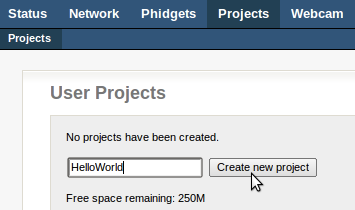

6. Create a new project on the SBC, in the web interface under Projects → Projects. Call it HelloWorld:

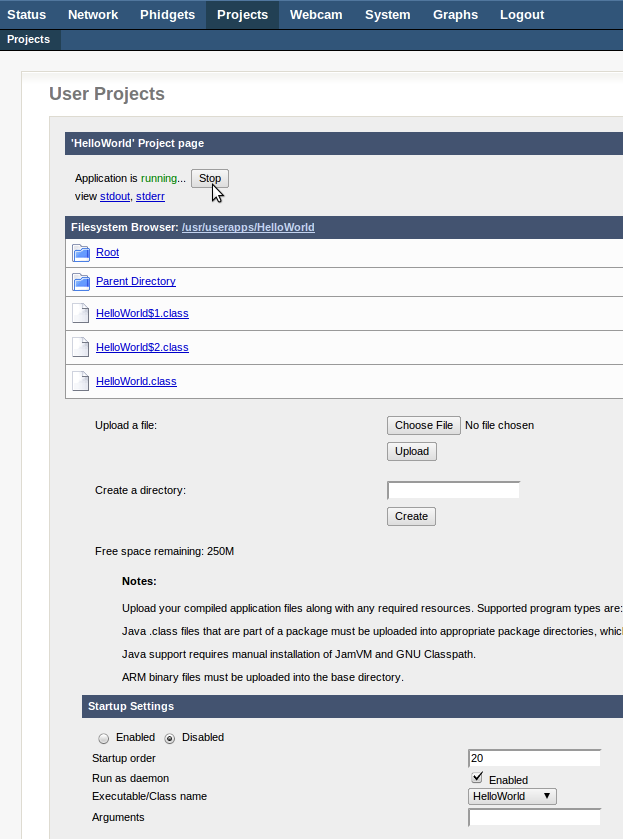

7. On the next screen, you will be prompted to upload your files. We will upload the three Java class files, and then click the Start button:

8. You'll note that as it runs, there are two links below the Stop button: One called stdout, which is Standard Output, and one called stderr, which is Standard Error. Usually, when you run a program on the command line, you see both standard out and standard error at the same time - i.e. you get all program output right there in your terminal or command prompt. But when running a program in the background, Linux splits the output up into normal output and error output as this is very useful for programming. Here, however, if you're not sure whether the program will run correctly, you should first check stderr to see if any errors were generated, and then check stdout to see if the output looks as expected.

To write your own Java program, follow the same process but use your own source code instead of the HelloWorld.java example.

Now that you have a running program, we offer additional help on running a program automatically using the web interface.

Program with SSH

Similarly to starting a program via the web interface, we use the Phidget Java HelloWorld example here.

Make sure you have Java installed on the SBC. To compile and run the HelloWorld example:

1. Open an SSH terminal to the SBC

2. Download the Phidget Java Examples to the SBC, using #wget (you may need to install wget using apt.)

3. Unpack the examples using unzip (you may need to install unzip using apt.)

4. The location of phidget21.jar on the SBC is /usr/share/java/phidget21.jar. Within the unzipped example directory, compile the HelloWorld.java example:

javac -classpath .:/usr/share/java/phidget21.jar HelloWorld.java

5. To run the {Code|HelloWorld}} program, use:

java -classpath .:/usr/share/java/phidget21.jar HelloWorld

Now that you have a running program, you'll probably want to learn to run this java program automatically.

Permissions Note: If you're used to using Linux with Phidgets already, you'll probably notice that you don't need to switch into root using sudo on the SBC in order to run programs. This is because you already are running as root, not because the udev rules are set up. So if you set up another user, or run a cron job as anything other than root or system, you'll need to add permission for the Phidget program to run in your udev rules.

Editing Notes

When you're not just using pre-written source code, and you're writing code actually on the SBC itself, you'll probably want to use nano. Other terminal editors on the SBC include vi which is already installed, and emacs, which you can install using apt. Both vi and emacs are much more efficient for the experienced user, but they contain modes and keyboard shortcuts that can seem strange or almost hindering to the casual user.

Regardless of which editor you choose to use, some of your keyboard habits may not transfer well. For example, in the Linux command line, the command Ctrl-C means stop the currently running program, (i.e. your open editor) not copy. Within most SSH terminals, you can copy and paste using the right-mouse button, and on some terminals (and all native Linux terminals) you can copy by simply highlighting text, and you can paste it using the middle (scroll) mouse button. On the other hand, if you write a program that hangs on the command line, Ctrl-C can actually be useful to terminate it.

Also Ctrl-Z does not mean undo, rather it is a reserved terminal command to run the current program in the background. This is useful because running a program in an SSH terminal simply hangs your SSH input until the program is done. So typing Ctrl-Z while the program is running frees up the command line for more input. If you accidentally hit Ctrl-Z while running an editor like nano, the editor will immediately exit to the command line, but it will not stop or lose your work. You can bring it back up by using the fg (e.g. 'foreground') command, like fg nano, and this will automatically bring your nano process back to the front.

Running a Program Automatically

Via the Web Interface

To use this method, you must have created the program you want to run as a project in the web interface.

In the web interface, go to the Projects tab, and click on the project you would like to run. Near the bottom of the project page (the one with the Start and Stop buttons at the top), there will be a section called Startup Settings. You can see a screenshot of the whole project page, including these settings, in the web interface project section.

Select the Enabled radio button. The other defaults should be fine, unless you specifically know otherwise:

- For boot order, lower numbers boot first. Booting later means more programs are available for use.

- Run as a daemon starts the program as a daemon, which is a program that runs in the background. Unless you have explicitly written your program as a daemon, leave this checked. (If you don't know what a daemon is, don't worry, you haven't written one.)

- The Executable or Class name should be automatically sensed to be your main Java class

- Arguments are any command line arguments you need, just as you would type them into the command line

Note: Your program must be very, very stable to run properly via the web interface. Imagine your program running continuously for days, or months on end. Any memory leaks, over time, will render your program (and the SBC) unusable until a reboot. Counts or other variables that increase and never reset may create a segmentation fault eventually.

If, for stability purposes, you want your program to start, run for a little while, and then exit so that the SBC operating system can clean up the memory each time, you'll probably want to use Cron to run your program instead.

Via Cron

Cron can automatically schedule programs - known as 'jobs', or 'cron jobs' - at most once per minute. Less often than that, it is very flexible, allowing you to run it on certain months, weekdays, hours, etc. Cron simply reads a special file (your crontab) and runs whatever programs are listed, with whatever timing they are listed with. The cron program runs all the time in the background, making it what is known as a Linux daemon.

If you need your program to run more often than once per minute, have the program schedule itself while still running. For example, to run every five seconds, run a fast loop, and sleep for five seconds. Do this twenty times and exit. Then schedule this once per minute using cron, and your program will in essence run every five seconds.

Setting up a cron job simply entails editing your crontab file.

First, you'll probably want to specify your default editor to be nano. Otherwise it will default to vi and you'll have to figure out vi in order to add lines to your crontab:

export EDITOR=nano

Then, to edit your crontab file, simply type:

crontab -e

Each line of the crontab file is one scheduled job. Lines that start with a hash "#" are comments and are ignored. There is an example line in the crontab, and a reminder line at the very end. Essentially, each line should contain:

minute hour dayOfMonth month dayOfWeek command

Where:

commandis the program you want to run (with absolute path, and arguments)- For example,

./myprogram argument1won't work, but/root/code/myprogram argument1will

- For example,

- Each time argument is either a number, a list of numbers separated by commas, or an asterisk

- For example, * * * * * means every minute for all days and months, 0,30 * * * * means every thirty minutes for all days and months

If you already have jobs scheduled, you'll see them in the file that comes up. You can edit, add, or delete.

After you save, you'll see a little message back in the terminal that says the new crontab file was installed, and it is now scheduled! Cron always starts every boot, and so if you have edited and installed your crontab as above, the scheduling of your program will start properly even after a reboot of the SBC. However, if you are having strange scheduling problems, you may want to familiarize yourself with the software details of how the SBC as a whole determines the current date and time.

My Cron Job Doesn't Work!

It is actually very common for a script or program to work on the command line but then not work as a cron job. The most common reason for this, by far, is that you specify relative paths in your program to access files rather than absolute paths. For example:

code/project.cis a relative path (bad for cron)/root/code/project.cis an absolute path (good for cron)

The cron jobs are not executed from your home directory, or your code directory, so they will not be using the same location you may be using to test your code. So always use absolute paths.

Another common reason is you may be using environment variables or other settings that are true in a terminal but are not true by default in the raw system. You can end up taking many things for granted in a shell, for example the shortcut "~" means home directory in a shell, but not by default in the raw system. The things that get loaded for a shell (but which are not present in the raw system) are:

- The settings loaded by

/etc/profile - Any settings in

~/.bashrc, which is nothing by default on the SBC

On a full Linux operating system, you would use the logs written to by cron to find the error output and debug it. On the SBC, however, cron does not write logs (otherwise, these logs would eat up the SBC memory very quickly even for routine jobs). For short-term debugging, you can write output from your program to a file, and read that file afterwards to figure out what your program is doing.

Via a Boot Script

If you want to run your program constantly and for it to start at boot like the web interface would do, you can install your program into the boot order using a script. This is a somewhat involved process, and you should be familiar with shell programming in Linux. For this process, we only offer a similar example which installs and runs the program phidgetwebservice21 within the boot sequence.

Using USB Data Keys

After plugging the USB key in, it won't just appear on your desktop, so to speak, so you'll need to figure out where you can read and write to it within the SSH directory structure.

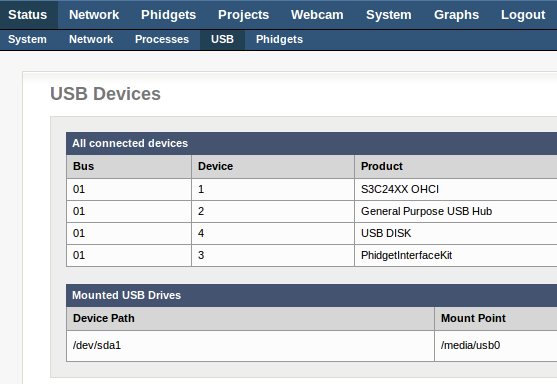

The web access program can help with this. After you plug a USB key in, it will show up under Status → System. Or, the USB key and all other attached devices can be seen at Status → USB:

In the screenshot above, you can see that the USB key is located in /media/usb0.

Alternately, you can use the SSH command mount, and the searching program grep which will filter the response of mount and only return the lines with your search term (usb):

root@phidgetsbc:~# mount | grep usb

/dev/sda1 on /media/usb0 type vfat (rw,noexec,nodev,sync,noatime,nodiratime)

In this case, the USB key can be written to and read from using the /media/usb0 directory. Copying a file to /media/usb0 will copy a file to the USB key. The same goes for removing, renaming, opening files within your program, etc.

Note: Mount points like /media/usb0 should not be hard-coded into any of your programs. (See the Common Problems and Solutions section for more information.) If you need to obtain the mount point for a freshly mounted USB key within your code, have your code obtain the mount tables and search on the device (e.g. /dev/sda1 or /dev/sdb1) and obtain the corresponding mounted /media/usbN location, where N is a number 0-9.

Saving and Retrieving Data

Over the Web (an SBC Webserver)

Backing Up Your Data

For the web interface, you can save and restore all web interface settings under the System → Backup & Restore tab.

To save the settings of what packages are installed for later re-installation, you can type:

dpkg --get-selections > installedPrograms.txt

Then save the file installedPrograms.txt externally. If you have to completely wipe the SBC, you can just reinstall the whole list by moving the installedPrograms.txt file back onto the SBC, and then typing:

dpkg –set-selections < installedPrograms.txt

apt-get dselect-upgrade

Also remember to externally save:

- Your

~/.bashrcsettings file if you've changed it - Your

crontabfile if you've edited it - Any data files or code you've created

It is important to save these settings often, and at points where you know the system is running well. It may be tempting to create a backup right before you wipe the SBC and start from scratch, but often the reason you are having problems then is some setting or change, and backing these up and reinstalling them will only reinstall the problem.

Troubleshooting

The SBC can be quite tricky to debug, because it is a complex and flexible computer. Common problems and solutions include:

- You can't find the SBC on the network at all - refer to the Initial Internet Setup section

- You have changed some setting or file such that the SBC doesn't run anymore, or doesn't run as expected - refer to the Recovery section

If you are having trouble using Phidgets on the SBC, you should go through the Troubleshooting section on the general Linux page. Some of the problems on the Linux page (such as library problems) are easier to fix by simply working through the Recovery section when they occur on the SBC.

If your problem doesn't seem to be fixed by these steps, or the information within this guide, please ask us!

Initial Internet Setup

To set up the SBC, you almost always need a wired Ethernet connection with DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol), and without a firewall. Even if you do not have this type of a connection at home, these types of connections are very common at both offices and universities. On a Windows or Mac OS computer, you can bring up the Phidget Control Panel as described in the SBC's Getting Started Page. Failing this, or on a Linux computer, we discuss some alternate setup methods in this section, but these can be difficult and fickle.

No Wired-Only Connection

Sometimes it can work to plug the SBC, using Ethernet, directly into an Ethernet port on your home wireless router. This is a very picky process, however, and can fail because:

- Some home and office routers place a firewall between wireless connections (clients) and wired connections (the local area network)

- Some home and office routers do not by default allow both Ethernet DHCP and wireless DHCP.

- Some routers and DHCP hubs only provide access to an internet connection, and do not provide local area network inter-connections (this is common on mobile device tethering hubs)

Routers are quite complex, and even with admin privileges it can be a painstaking process to find all the right firewall settings to turn off in order to allow two computers on the network to talk to one another, rather than just connect to the internet. This is why university or office networks are often ideal for the purpose of setting up the SBC, because these institutions depend on computers on a local network being able to talk together. Covering all of the different router configuration possibilities, and how to change them to make the SBC work, is essentially impossible.

The good news is that if you can find an Ethernet DHCP connection just once for a short time, you can use that connection to enable wireless and set up as many wireless DHCP connections (with passwords) that you need on the SBC. Once wireless is enabled and set up, you can take the SBC home to your wireless router and the SBC will automatically seek out and connect to its remembered networks as they appear. At that point, you can also use wireless like a normal internet, web interface, and SSH connection.

No Link Local Addressing

If you have a wired DHCP connection, no firewall, and no link local addressing (e.g. bonjour or avahi is not installed) then you will need access to the DHCP router logs. From the router logs, you should see the connection (or attempted connection) by the SBC within the logs. From that log entry, you should either be able to determine the IP address for the SBC, or see what happens when the router blocks access. The IP address can be used in place of the link local address for both the web interface and for SSH.

No DHCP

The SBC will first try to use DHCP, but then it will revert to responding to a link local address under bonjour and avahi. If you are depending on this, please wait at least three minutes after the SBC boots for the SBC to fail in obtaining a DHCP connection and properly revert to link local addressing.

If you have a static IP setup, and want to use link local addressing rather than accessing the router logs, this should usually work by default on Windows and Mac OS (e.g. type the address such as phidgetsbc.local into a web browser). If it doesn't work automatically, there is not much you can do and you should seek out a wired DHCP connection elsewhere.

On Linux, it also should work by default, but you have the additional option of explicitly adding routes that look within the default network settings for the SBC. From a terminal (as root), type:

route add -net 169.254.0.0 netmask 255.255.0.0 dev eth0 metric 99route add default dev eth0 metric 99

You can also compile and use the phidgetsbclist.c example (use the provided Makefile, don't use gcc) in the Phidget Linux Libraries package, under the examples folder. This will allow you to see if the SBC is detected on the network at all.

Recovery System

You can either boot the SBC into recovery mode and attempt to recover files and settings, or you can completely wipe the SBC by performing a factory reset.

Partial Recovery

The recovery system can be entered in two ways:

- From the

System → Backup & Restoreweb interface page. - By holding down the reset button for 20+ seconds - until the green light has switched from flashing slowly to flashing quickly.

The recovery system runs an SSH server where the username and password both are root.

If the main filesystem has been damaged/misconfigured in such a way that it won’t boot, you may be able to fix the issue or recover important files before running a full factory reset. From an SSH connection to the recovery system, you can mount the main root filesystem with the following commands (assuming it’s not damaged):

ubiattach /dev/ubi_ctrl -m 6

mount -t ubifs /dev/ubi0_0 /mnt

Factory Reset

This restores the kernel and root filesystem from backup, overwriting any changes that may have been made. This can be enacted one of two ways.

- Holding down the reset button for 10 seconds

- Via the web interface, under

System → Backup & Restore → Go button

Updating Your SBC

If you've owned your SBC for a while and want to update your packages, you can run:

apt-get update

apt-get upgrade

...to update your software source list and then update to the latest version of all installed software.

To update the SBC software itself (e.g. the kernel), it is easiest to use the web interface, under System → Backup & Restore → Go button, to enter a page that will give you the option to update. You will need to have an update file on a USB key inserted into the SBC, of type:

- UBI Image (system_ubi.img), or

- Kernel image (uImage), or

- Phidget Upgrade package containing both UBI and Kernel images (phidgetsbc*.bin)

These are either obtained from the Phidgets website, or are a custom kernel / filesystem that you can create yourself, if you are experienced.

The reason why this information is in troubleshooting is that you should certainly back up your system before trying this. And, it is quite rare to need to upgrade the kernel or filesystem on the SBC, so something serious should be going on before you attempt it. Try using the recovery system first.

Programming Languages

Now that you have the basic libraries installed, you can pick your language and begin programming!

If you are not using the webservice (discussed below) to control a Phidget over a network, your next step will be to delve into the use of your specific language. Each page has its own set of specific libraries, code examples, and setup instructions.

On Linux, we recommend the following languages:

These languages may also run on the SBC, but we do not offer SBC support for them:

Webservice

Advanced Uses

Using a Different Wireless Adapter

The support for the wireless adaptor that Phidgets sells is written into the SBC kernel. Hence, we do not support using other adaptors.

However, Linux is very flexible, and it is possible (though not easy) to write a custom kernel for the SBC and add support for a new wireless adaptor. We can't help you with this, but we do provide some basic guidelines for building your own kernel.

Using a Different Webcam

In addition to the webcam that Phidgets sells, you have the option to use many different webcams with the SBC. There is a long list of compatible webcams.

The common thread for these webcams is that they use UVC - the USB Video Class - drivers for Linux. You can then use mount to find out what video device your webcam is mounted under.

Taking Pictures With the Webcam

Probably the most straightforward way to use a webcam for pictures rather than video is to use the opencv library. You can get it by:

apt-get install opencv

The opencv libraries can also be used within Python, by installing the link between them:

apt-get install python-opencv

Then taking pictures from within code becomes quite simple. For example, in Python, taking and saving an image is four lines:

#! /usr/bin/python

import cv

# The webcam is located at /dev/video0

# OpenCV only needs the number after video

webcam = cv.CaptureFromCAM(0)

frame = cv.QueryFrame(webcam)

cv.SaveImage("image.jpg", frame)

For the complete OpenCV documentation, see The OpenCV Reference, and specifically the section on Reading and Writing Images.

Checking System Logs

Custom Kernel and Filesystem

You can compile your own kernel and flash it to the board. It is left up to the user to configure an appropriate cross-compiler for kernel development. You may also be able to compile a new kernel on-board.

Compiling a new, custom kernel is somewhat hard. If the SBC is your first experience with Linux, writing a custom kernel will be very difficult, and more probably impossible. We might be able to offer additional suggestions to people who have extensive experience in Linux already, but ultimately you're on your own here.

You may be able to write a custom kernel right on the SBC, but the easiest way is to develop the kernel on an external computer. And the easiest way to develop on an external computer is for that computer to also be Linux. On your external Linux system, you will need a cross-compiling toolchain for the ARM processor, which we briefly describe on the main Linux page.

Also on your external computer, you can download the SBC Kernel Development Package from the Phidgets website. This kernel development kit has a brief README file which describes how to obtain the proper kernel and patch, configure, customize, and build it.

After making your new kernel, you should have a uImage and modules target for your Makefile. At this point you can transfer your kernel files onto the SBC, make their targets, and transfer them into the nand memory. This involves erasing the old kernel, flashing the new kernel, installing the new kernel modules, and rebooting. From the SBC, in the kernel directory:

make uImage; make modules

flash-eraseall /dev/mtd3

nandwrite -p /dev/mtd3 arch/arm/boot/uImage

make modules-install

reboot

Custom kernels can also be flashed from the Recovery System.

If you need to create a root filesystem image, the filesystem type is UBIFS, and the commands to create it are:

mkfs.ubifs -m 2KiB -e 126KiB -c 4050 -r $ROOTFS/ system_ubifs.img

ubinize -o system_ubi.img -m 2KiB -p 128KiB -s 512 ubinize.cfg

Where ubinize.cfg contains:

# Section header

[rootfs]

# Volume mode (other option is static)

mode=ubi

# Source image

image=system_ubifs.img

# Volume ID in UBI image

vol_id=0

# Volume size

vol_size=64128KiB

# Allow for dynamic resize

vol_type=dynamic

# Volume name

vol_name=rootfs

# Autoresize volume at first mount

vol_flags=autoresize

You then flash ‘system_ubi.img’ (not ‘system_ubifs.img’) from the recovery system.

Again, like the custom kernel creation, the need to create a custom root filesystem is essentially non-existent except for those advanced users who already know they need it... and furthermore, you are almost entirely on your own.

Software Details

For even more advanced uses of the SBC, it may help to know the gritty details of the SBC software system.

- Operating System

- Debian/GNU Linux

- Kernel 2.6.X or higher (generally kept up to date with latest releases, use

uname -rto check the kernel version)

- Main Filesystem (rootfs)

- UBIFS (a raw flash type of file system)

- Mounted in a 460 MB Nand partition (in Read/Write mode)

- Kernel

- uImage format

- Has its own 3MiB partition on bare Nand

- Web Interface Scripts and Configuration Data

- Located in

/etc/webif - Modifying these scripts can be done; however, it is very easy to enter invalid data that could cause the system to behave unexpectedly or not boot.

- User Applications uploaded through Web Interface

- Located in

/usr/userapps

- Webcam Device Location

/dev/video0- Numbers increase with more webcams

- Date and Time

- Set using ntp (network time protocol) at boot.

- The ntp daemon continues to run in the background and will periodically update the clock

- The network keeps the SBC very close to real time.

- Also there is a real-time clock with battery backup which will preserve date/time across reboots, power removal. :The real-time clock is synced to system time during reboot/shutdown.

- If power is unplugged suddenly, and the network not restored, the real-time clock may not have the correct time.

- Wireless Networking System

- Wireless adapter support for the wireless adapter that Phidgets sells is written into the kernel

- It supports WEP and WPA

- It is best configured through the configuration interface.

- Nand Layout

- The board contains 64MB on Nand. This nand is split into 7 partitions as follows:

- 0: u-boot size: 256K Read Only

- 1: u-boot_env size: 128K Read Only

- 2: recovery_kernel size: 2M Read Only

- 3: kernel size: 3M Writable

- 4: flashfs size: ~3.625M Read Only

- 5: recovery_fs size: ~ 43M Read Only

- 6: rootfs size: ~ 460M Writable

- The final size of flashfs/recovery_fs/rootfs depends on the image size at production, and on the number/location of bad blocks in the NAND.

- Note: U-Boot and recovery kernel and filesystem cannot be written from Linux - this is a safety measure.

- Boot Process

- From power on...

- 1. Processor loads first 4 bytes from NAND into Steppingstone and runs it.

- 2. Steppingstone sets up RAM, copies u-boot from NAND into RAM and runs U-Boot.

- 3. U-Boot initializes the processor, sets GPIO state, etc., copies the linux kernel into RAM, sets up the kernel command line arguments, checks that the kernel image is valid, and boots it.

- 4. Linux boots, bringing up USB, Networking, NAND, etc. and then mounts the rootfs NAND partition on /.

- 5. init gets run as the parents of all processes, as uses the /etc/inittab script to bring up the system. This includes mounting other filesystems, settings the hostname, and running the scripts in /etc/init.d, among other things.

- 6. inittab then turns the green LED on.

- 7. inittab then sets up a getty on the first serial port, ready for interfacing using the debug board.

Common Problems and Solutions

USB Memory Key mounting: Sometimes USB Memory Keys mount at more than one location

When you insert a memory key, the SBC will load it as a device (e.g. /dev/sda1) and it will also mount the key for reading and writing within the /media/ directory. The /media/ directory version will be called something like usb0.

At times, an inserted memory key will get mounted in more than one location. You can observe if this occurs by checking the currently mounted devices with the command mount:

root@phidgetsbc:~# mount

tmpfs on /lib/init/rw type tmpfs (rw,nosuid,mode=0755)

proc on /proc type proc (rw,noexec,nosuid,nodev)

sysfs on /sys type sysfs (rw,noexec,nosuid,nodev)

udev on /dev type tmpfs (rw,mode=0755)

tmpfs on /dev/shm type tmpfs (rw,nosuid,nodev)

devpts on /dev/pts type devpts (rw,noexec,nosuid,gid=5,mode=620)

rootfs on / type rootfs (rw)

procbususb on /proc/bus/usb type usbfs (rw)

/dev/sda1 on /media/usb0 type vfat (rw,noexec,nodev,sync,noatime,nodiratime)

/dev/sda1 on /media/usb1 type vfat (rw,noexec,nodev,sync,noatime,nodiratime)

You will note that the same device (/dev/sda1) is now mounted at both /media/usb0 and /media/usb1. To fix this problem as it occurs, you can use umount (notice there is no letter 'n') to unmount the second instance:

root@phidgetsbc:~# umount /media/usb1

In practice, this should not be a problem, because writing to or reading from either usb0 or usb1 will have the same effect on the memory key. However, if you hard-code a media location into your program (i.e. expecting /media/usb0 to be the first USB key you insert and /media/usb1 to be the second key) your program will sometimes work and sometimes fail.

To get around this within code, find the mount point for each device as it appears. The devices, such as /dev/sda1 will always refer to the actual memory key. But, they cannot be written to directly without being mounted, so you will have to parse the mount table (what is returned from mount) within your code to find the device and its corresponding mount point.

This is a problem with the standard embedded Debian automount program, and we have no known fix.