|

Notice: This page contains information for the legacy Phidget21 Library. Phidget21 is out of support. Bugfixes may be considered on a case by case basis. Phidget21 does not support VINT Phidgets, or new USB Phidgets released after 2020. We maintain a selection of legacy devices for sale that are supported in Phidget21. We recommend that new projects be developed against the Phidget22 Library.

|

General Phidget Programming: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

This page presents the general '''concepts''' needed to write code for a Phidget. | This page presents the general '''concepts''' needed to write code for a Phidget. | ||

By this point, you should have installed the drivers for your [[Software Overview#Operating System Support| | By this point, you should have installed the drivers for your [[Software Overview#Operating System Support|operating system]] and the libraries for your [[Software Overview#Programming Language Support|specific programming language]]. | ||

==The Basic Functions== | ==The Basic Functions== | ||

Revision as of 16:38, 8 November 2011

This page presents the general concepts needed to write code for a Phidget.

By this point, you should have installed the drivers for your operating system and the libraries for your specific programming language.

The Basic Functions

To use your Phidget within code, you'll want to:

- Create a Phidget software

object, which gives you access to the functions specific to that device - Open the Phidget using the

object - Detect when a Phidget is attached (plugged in) by using the

object - Use functions that the

objectprovides, like turning on LEDs, reading sensors, triggering events on data change, etc - Close the

object, when you are done

Creating a Software Object

Phidget devices are controlled using software objects. All software device objects have a common API and set of functions that allow you to open it, close it, and set a few listeners to general events such as attach (plug in), detach (unplug), and errors.

But when you create an actual software object, it is a software object specific to your device.

For example, in Java:

// Create a new Accelerometer object

AccelerometerPhidget device = new AccelerometerPhidget();

// Create a new RFID device object

RFIDPhidget device = new RFIDPhidget();

Or in C:

// Create a new Accelerometer object

CPhidgetAccelerometerHandle device = 0;

CPhidgetAccelerometer_create(&device);

// Create a new RFID device object

CPhidgetRFIDHandle device = 0;

CPhidgetRFID_create(&device);

Each software object has an API and available functions which are specific to that device. For example, the RFID device API includes a function to turn on the RFID antenna. The accelerometer device API includes a function to set the sensitivity on each axis.

Opening the Phidget

Phidgets can either be opened when attached directly to a computer, or they can be opened remotely using the Phidget Webservice. This section deals primarily with opening Phidgets directly.

Once you have created your software object for your specific type of device, you can call the open() function in your language on that object. For example, in Java:

device.open();

Or in C:

CPhidget_open((CPhidgetHandle) device, -1);

All specific language calls can be found in the API documentation located on each individual language page.

The open() function in any language opens the software object for use, not the hardware itself. Having the software "open" before the hardware means that the software can capture all events, including multiple attach (plug in) and detach (unplug) events for one open() call.

Attaching the Phidget

Physically, attaching a Phidget means plugging it in. In your code, you can detect an attachment either with an event in event-driven programming, or waiting for it, in logic programming.

Event Attachment

For example, to use an event to detect attachment in Java:

// After creating a Phidget object called "device":

device.addAttachListener(new AttachListener() {

public void attached(AttachEvent ae) {

System.out.println("A new device has been plugged in!");

}

});

Or to use an event to detect attachment in C:

int AttachHandler (CPhidgetHandle device, void *userData) {

printf("A new device has been plugged in!");

return 0;

}

// .....Then, in the main code after creating a Phidget object "device":

CPhidget_set_OnAttach_Handler((CPhidgetHandle) device, AttachHandler, NULL);

Both of the code snippets above do the same thing. The function AttachHandler(...) is called automatically when a device is plugged in.

You will want to attach events (via addAttachListener() above, for example) before you open the Phidget object. Otherwise, triggered events may be lost.

This method for using events to detect attachment can be expanded to other events and more complex control flow. Where possible, all example code downloadable from the specific language pages shows event-driven programming.

Wait for Attachment

Waiting for attachment is a straightforward process. Your code does not handle events, it simply waits for a device to be plugged in before moving on and doing something else.

For example, in Java you wait for attachment on a created and open software object (called device) like this

// Wait until a device is plugged in

device.waitForAttachment();

Or in C (again, device has been created and opened) :

int result;

// Wait up to 10000 ms for a device to be plugged in

if((result = CPhidget_waitForAttachment((CPhidgetHandle) device, 10000))) {

// No attachment, error

}

// Successful attachment

So, unlike the event model above, a Phidget software object should be open before waiting for a device to be plugged in.

Do Things with the Phidget

After you have a Phidget software object (named, for example, device as above) that is:

- Created

- Properly attached to any events

- Opened

- Attached (plugged in)

...Then, you can actually call function to turn LEDs on, change output state, read data from sensors, etc.

The thing you probably want to do with your Phidget is read data from its sensors, say, a sensor plugged in to an <span style="color:red;"Interface Kit 8/8/8. You can do this either

int val;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

CPhidgetInterfaceKit_getSensorValue(phid, 0, &val);

printf("Value: %d\n", val);

}

The things you can do with your particular Phidget are many and varied, so you probably want to refer directly to the API for your device.

We provide both documentation on the raw API for each programming language as well as a language-independent description of the calls for each device.

- Read the raw API list on your your specific programming language page, in the Getting Started section.

- Read the high-level API description for your hardware on your specific Phidget device page.

Close the Phidget

When you are finished with the Phidget software object at the end of your program, you should close and (in some languages) delete it.

For example, in Java:

device.close();

device = null;

Or, in C:

CPhidget_close((CPhidgetHandle) device);

CPhidget_delete((CPhidgetHandle) device);

Putting It Together

User and device actions can be handled by either:

- Letting the program tell you when they happen and then doing something (event driven code)

- Polling for things to happen then doing something (logic code)

The style of programming you choose (and hence the language you might prefer) would depend on what you want to do with the Phidget. The two sections, Event Driven Code and Logic Code below give benefits, drawbacks, and general examples of each style.

The styles can also mix. For example, you can take a defined set of steps at first such as turning on an LED or antenna (logic code) and then doing nothing until an output change event is fired (event code).

With languages that support both styles, you can mix and match. For languages that support only logic code (see the Language Support Categories above) you can only use the logic paradigm style.

Examples in pseudo-code are given below for each style type so you can see how your language choice can affect your code design.

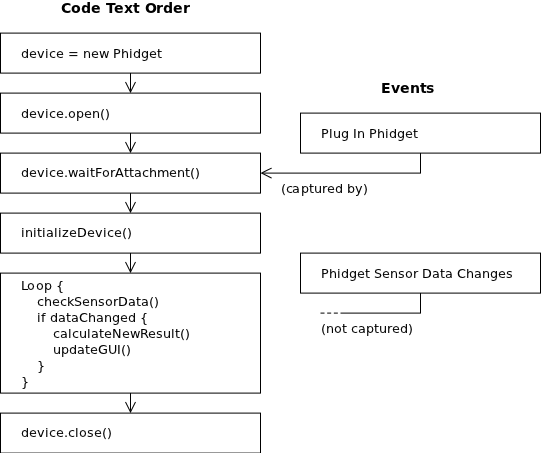

Logic Code

Logic code has use for:

- Simple, single-device applications

- Non-GUI applications (GUIs usually are event driven)

- The user driving the device rather than listening to it

Logic code is relatively easy to design well. For example, using the create, open, attach, do stuff, and close concepts introduced above, logic code to handle a Phidget might be written like this:

Although this design does not explicitly capture every event that fires when data or input changes, by polling the device often enough no data will be lost.

However, logic code cannot handle constant, asynchronous events as cleanly as event driven code can.

These designs can be mixed. So, if you find that in logic code you have a highly complex if loop driving your program, you should consider changing some of it to event driven code. This type of awkward if-loop might look like this:

Create Device Software Object

Open Device

Loop Until Exit Requested {

if No Device Attached {

Wait For Attachment until Timeout

if Wait Timeout Reached {

break

} else {

Initialize Device

}

} else { // Device Is Attached

if Device Data Type 1 Changed {

Do Something

}

if Device Data Type 2 Changed {

Do Something Else

}

// ... More data change functions here

}

Collect User Input

}

Close Device

Delete Device

On the other hand, you can probably see that if your language does not give the option for events, you can use this structure to mimic what events would enable you to do.

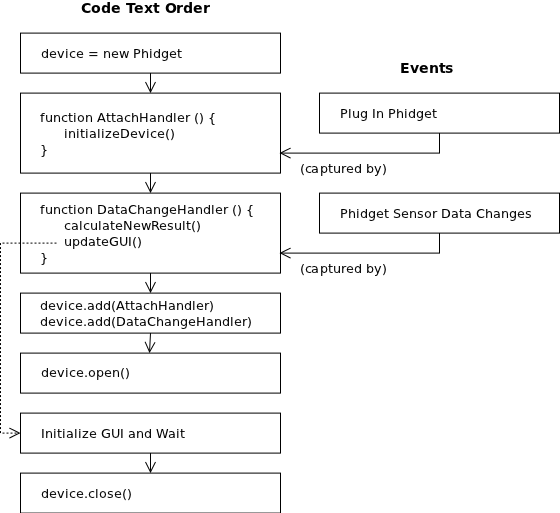

Event Driven Code

Event driven code allows for clean handling of complex, asynchronous programs:

- Handling multiple Phidgets

- Handling active plugging or unplugging of the Phidget (multiple attach and detach events)

- Working behind a GUI, as many GUIs are already event driven

- Capturing all sensor data - or input and output - without constantly polling

Without event driven code, you will need to constantly poll the device to see if any state has changed. If you poll at a slower rate than your input or output changes, you will not capture all data.

However, event driven code is usually not as useful or efficient for:

- Only one open and close event

- Using only one device

- Having the user (or program) put changes onto the device (in contrast to reading data from the device)

Event driven code is relatively hard to design well. It may help to draw out a flowchart, state machine, or at least a pseudo-code outline of your system design and all events you wish to handle before writing code.

The code examples given for each specific language use events if they are supported by the language.

Using the create, open, attach, do stuff, and close concepts introduced above, event code to handle a Phidget might be written like this: